I attended Air Force Officer Training School (OTS) in 1984. That's where, for twelve weeks, they tell you to do seemingly meaningless things and expect you to do them perfectly. Not almost perfectly, but perfectly.

There were two officer trainees (OTs) assigned to each dorm room in which there were two bunks, two wall lockers, two chests of drawers, and two desks with chairs--that's it; no other furniture was authorized. The exact placement of those furniture items was specified. We were also allowed a very limited list of personal items, and the exact placement of those items was also specified.

Instilling "attention to detail" in the trainees is the official reason for requiring that OTs arrange their environment in the specified way. The training was enforced and reinforced by a system of demerits administered by the flight commander--a commissioned officer who was responsible for the training of the 20 or so members of his flight.

Captain Weiss was our flight commander, and he inspected our rooms each day while we were out, giving demerits for each deviation from the standards. Your freedom, or lack of it, for the weekend was determined by the number of demerits you accumulated during the week. If your demerit count did not decline each week you could be "eliminated from training" for "failure to adapt to military training." Nobody wanted to be thrown out as we had worked too hard to get in--there were ten applicants for each OTS slot.

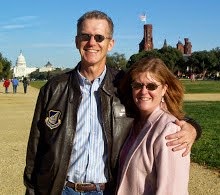

All uniforms, toiletries, etc. were arranged in the wall locker and chest of drawers in a particular way. The only personal item that could be displayed in plain sight was a framed photo that was to be placed in a precise location on the desk. I, of course, had a photo of my family displayed.

Two of the guys in the flight, Dave Cross and Scott Hubbard, were roommates, and neither had a significant other. But neither wanted to forego his OTS-given right to display that one personal item. At their first opportunity they went to the base exchange to buy a picture frame for each of them. As you have no doubt seen, frames come with pictures of models in them with the brand, size, and other information overprinted on the picture. Each of them selected a frame with a photo of a comely young woman in it.

Back in their room, they took the manufacturer-provided photos out of their frames and wrote inscriptions on them. Dave wrote on his, "To Dave, With all my love forever, Yours alone, Barb". Scott inscribed his with, "To Scott, You're the only one for me, Love, Barb". They put the photos back in the frames and proudly placed them on their desks.

Oh to have been a fly on the wall when Captain Weiss noticed that the frames were different, but the pictures were identical.